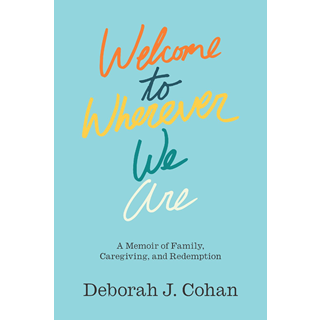

Deborah J. Cohan

Years ago, I attended a lecture given by the psychologist Carol Gilligan, and she said, “The thing about patriarchy is that it takes place in the midst of intimacy.” I think the reverse is also true, that intimacy takes place in the midst of patriarchy. She went on to say, “The ability to tell our story is interrupted by trauma.” Patriarchy. Intimacy. Ability. Tell. Story. Trauma. Trauma disrupts ability. Trauma shuffles, scrambles, and pulverizes story. Trauma dislocates, dislodges, and decimates voice.

I think trauma also makes story and voice possible . . . eventually.

Driving back from Mount Pleasant one Monday morning after alternately lazing around with Mike on the beach, in bed, and on a hammock all weekend, something my childhood friend Erica said to me weeks earlier hit me like a ton of bricks. She and I had been on the phone talking about a writing conference I had attended where I felt that someone had very much misinterpreted my writing. Stunned, Erica said, “I can’t believe she didn’t get it; it’s just about a girl who tried to do the right thing by her dad.” And then smack in the middle of that commute back to Bluffton, it occurred to me that was exactly it: I still am a girl trying to do the right thing by my father, both in writing and in life. I am aware that writing about his terrible qualities possibly makes me look like a fool for still adoring and missing my father. But you must understand my dad’s erratic meanness, which was all mixed up with his erratic kindness. The erratic nature of it all actually became predictable—predictable erraticness, erratic predictability

The phone rings. My machine picks up.

“Hi, this is Deb. I can’t come to the phone right now, but please leave a message, and I’ll call you back as soon as I can. I look forward to connecting with you soon.

Beep.

“Hi, Deb, it’s Dad. I hope . . . you’re the best . . . I can’t believe you . . . why did you . . . how could you . . . how dare you . . . you little shit . . . Beep.”

Play. Believe it. Rewind. Don’t believe it.

Play again. Don’t believe it. Rewind. Believe it.

Delete? Save?

Delete.

Some things can be deleted. Just often not the memory.

One night, long after my parents and I moved out of the house on Morley Road in Cleveland and I was living in Waltham, Massachusetts, I decided to call our old number, just to see who would answer. I dialed and got the recording that the number was disconnected. Disconnected. Well, yes, of course. Actually, the wires had been tangled for years. Crisscrossed. Fried. Burnt. People tripped over cords. Over discords. Who was even listening anymore?

Connected. Disconnected. Dis/connected.

My father was financially generous, but he was also financially controlling in ways that came with strings attached and left me feeling beholden to him. It was August 2000, almost a year after my parents split up, and I was working on my doctorate. He had offered to help me pay for health insurance, so one night we were on the phone figuring out the best arrangement, and I suggested he go to the bank and put the deposit in all at once, just to make things easier on him. He replied, “You’d make my life easier if you’d commit suicide.” I was speechless. He went on to say, “Your mother is a slut. She ran off to fuck someone she has not seen in fifty years.”

Yes, my mom had left my dad and immediately ran back into the arms of her first love, Allan, a guy she met at overnight camp when she was fourteen years old. At the time, I couldn’t understand it either, and I—and everyone else—wondered if theirs was an affair that had simply lingered on for years. My mother has always claimed that it was not, that they truly reconnected in 1999 after Allan lost his wife to complications from chemotherapy and a mutual camp friend told him that my mother was soon to be single. And I remain moved by what my mom has said to me over the years—that Allan is the first man she ever really loved. So at sixty-four years old, when my mother moved in with Allan, she got to come full circle.

There have been times I’ve wondered about the real sequence of things, but in reality, I’ve never really cared.

I understand that monogamy is a tender social construct that is often hard to uphold, and I would have forgiven her if having an affair was part of the story. In fact, my dad’s behavior was all too often so impossible that I questioned her loyalty and why she stayed; I never really understood them together. Now at forty-nine, I understand it better, through the prism of my own love for my dad, my own loyalty to him, even amid all that went on. And at the same time, their union made sense. When I was a child, it was my definition of family.

What was complicated—and remains so even now—was how I learned that my mother made such a huge life change, leaving Cleveland after being there all her life. Before my mother leveled with me that she had already up and moved to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to be with Allan, I had already discovered it for myself. My parents’ marriage was a second marriage for both of them, and they were each relatively familiar with the names of each other’s old flames. Soon after my parents split up, I was in Cleveland to help my dad clear everything out of the family house, prepare for an estate sale and house sale, and get situated in his new apartment. It was then that he shared with me that he suspected that my mother had reunited with Allan and that he remembered that Allan lived somewhere in Massachusetts. My dad knew Allan’s last name, knew he was a dentist, and thought he was possibly retired. They had all gotten together when I was a very little girl when Allan had come to Cleveland for some sort of dental conference. My father believed that Allan was always pining for my mom. I decided to call information for Allan’s number to either hear what his voice sounded like or see if my mother would answer the phone. It was about 9:30 p.m.; she answered and sounded half asleep. I nervously hung up. I got my answer.

Excerpted from Welcome to Wherever We Are: A Memoir of Family, Caregiving, and Redemption by Deborah J. Cohan. Published by Rutgers University Press on February 14.